In the late 90’s, I was a primary school student. I remember reading a book while the teacher called out names for the daily register. She called out my name and I didn’t hear her, but when she finally managed to grab my attention, she wasn’t angry. She actually seemed pleased. ‘I wish I could get that absorbed in a book’, she said.

Around the same time period, one of the most famous games in history was released – Final Fantasy 7. I was similarly absorbed by the long conversations between the characters, interactions that relied on text with no voice acting. (Tellingly, some have argued that the Final Fantasy series contains literary elements.) I recently rewatched a vital scene from 7 and noticed how Cloud’s dialogue suddenly overlaps Sephiroth’s ranting to convey a furious interruption, and how at another point Cloud’s words stay locked within a single text box, slowly moving up to give way to the next sentence rather than appearing in separate boxes. It’s strangely fitting for the emotional nature of the scene – the words feel agonised.

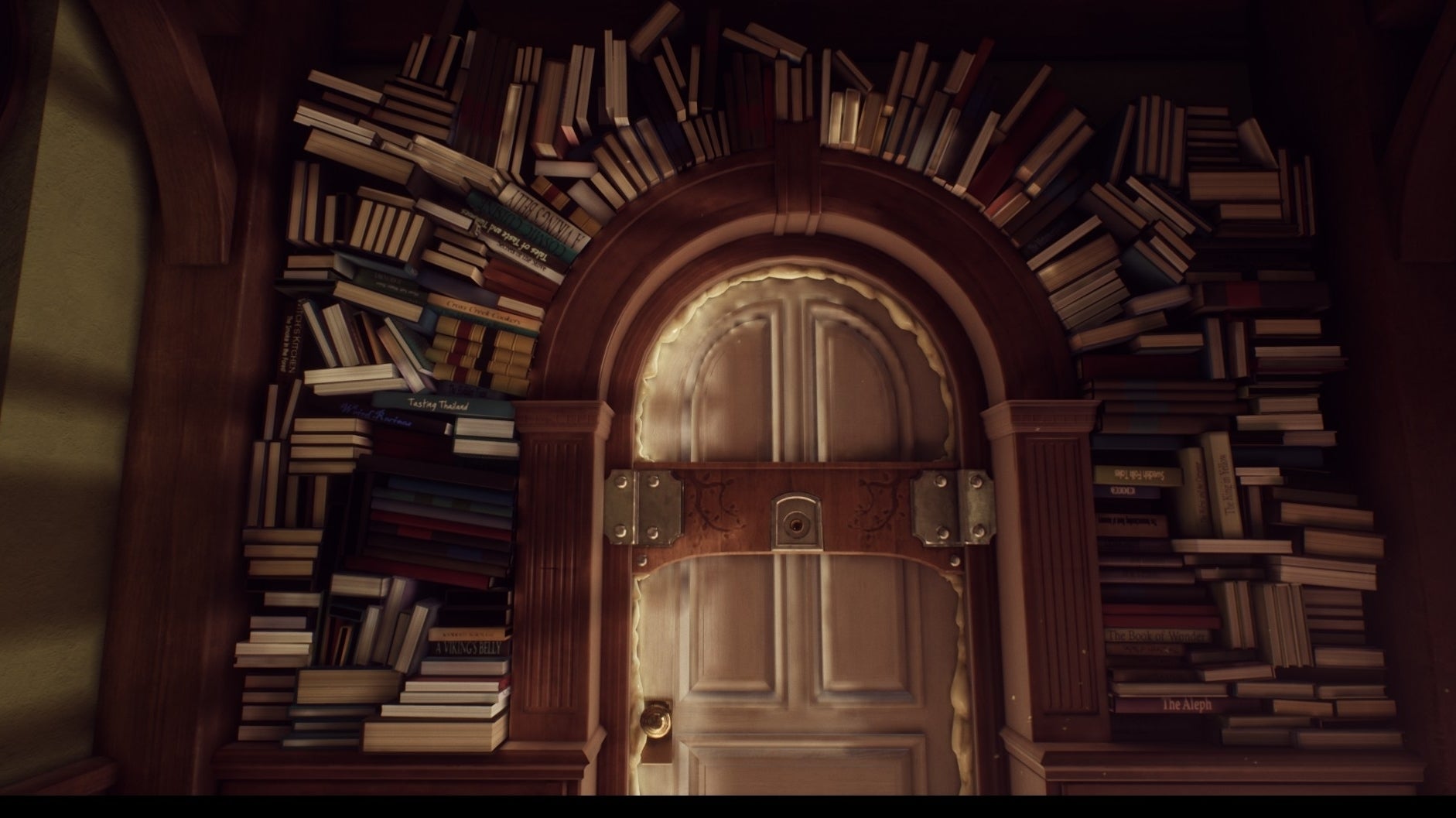

The more games I play, the more I come across developers using text in engaging, interesting ways. In some cases, as in the scene above, the key is the placement of text, something that What Remains of Edith Finch handles with particular skill. In Finch, the character you control narrates her feelings and thoughts to you in both voice and text form. The text, however, is treated in a playful fashion, appearing on objects and in areas that tend to be directly relevant to the words and the emotional associations in the scene. At one point your character’s lines appear over a gate before you: ‘I hadn’t been back since my brother Lewis’ funeral’. As you open the gate, the text shatters and lies at your feet, echoing the sensation of loss in its disarray. In another scene, you look at the front of your fridge and see a typical family picture pinned there with colourful magnets. Underneath the picture, text reveals itself: ‘But instead of a family, there were just memories of one’. After a moment it vanishes and leaves you with those memories.

So far I have touched on developers using placement of text as a creative technique in their work. But what about the use of straightforward prose in itself?

I recently played some of Lost Odyssey for the first time – it holds up well for an older game, but what actually ended up being the most striking aspect to me was its use of text. Every now and then you encounter actual short stories that refer to the background of the character you play. The prose (by Kiyoshi Shigematsu and translated into English by Jay Rubin) is some of the best that I’ve come across in the video game medium. While reading a lot of text while playing can sometimes feel dull – a lot of codex entries in RPGs fit this description for me – Lost Odyssey actually turns text into something that feels truly engaging, with pieces that are character-driven and deal with love and death. The protagonist is incredibly introverted during the normal gameplay, and so the prose pieces are used to open him up to the player by letting us indulge in his memories.